The Systematic Assimilation of Revolutionary Movements: How Authorities Transform Opposition into Integration

The Assimilation and cooptation of Revolutionary Movements: Synopsis

Introduction

Revolutionary movements have long emerged as responses to deep societal injustices, often confronting entrenched authorities in pursuit of radical change. While these movements initially aim to upend existing systems, a recurring pattern shows that authorities adapt, absorb, and ultimately assimilate these movements—transforming sources of challenge into instruments that reinforce existing power structures. This phenomenon, far subtler than outright repression, relies on processes of cooptation, institutionalization, and regulation that neutralize revolutionary ambitions.

Theoretical Foundations

The concept of cooptation, as analyzed by sociologist Philip Selznick, describes how institutions integrate threatening elements by absorbing their leaders and ideas, thus averting destabilization. Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony provides a vital lens here, emphasizing how authorities secure consent from the governed not only through force but also through cultural and institutional integration. Such processes ensure that even the most radical social movements, over time, may contribute to the stability and legitimacy of systems they were meant to disrupt.

The Four-Stage Model of Assimilation

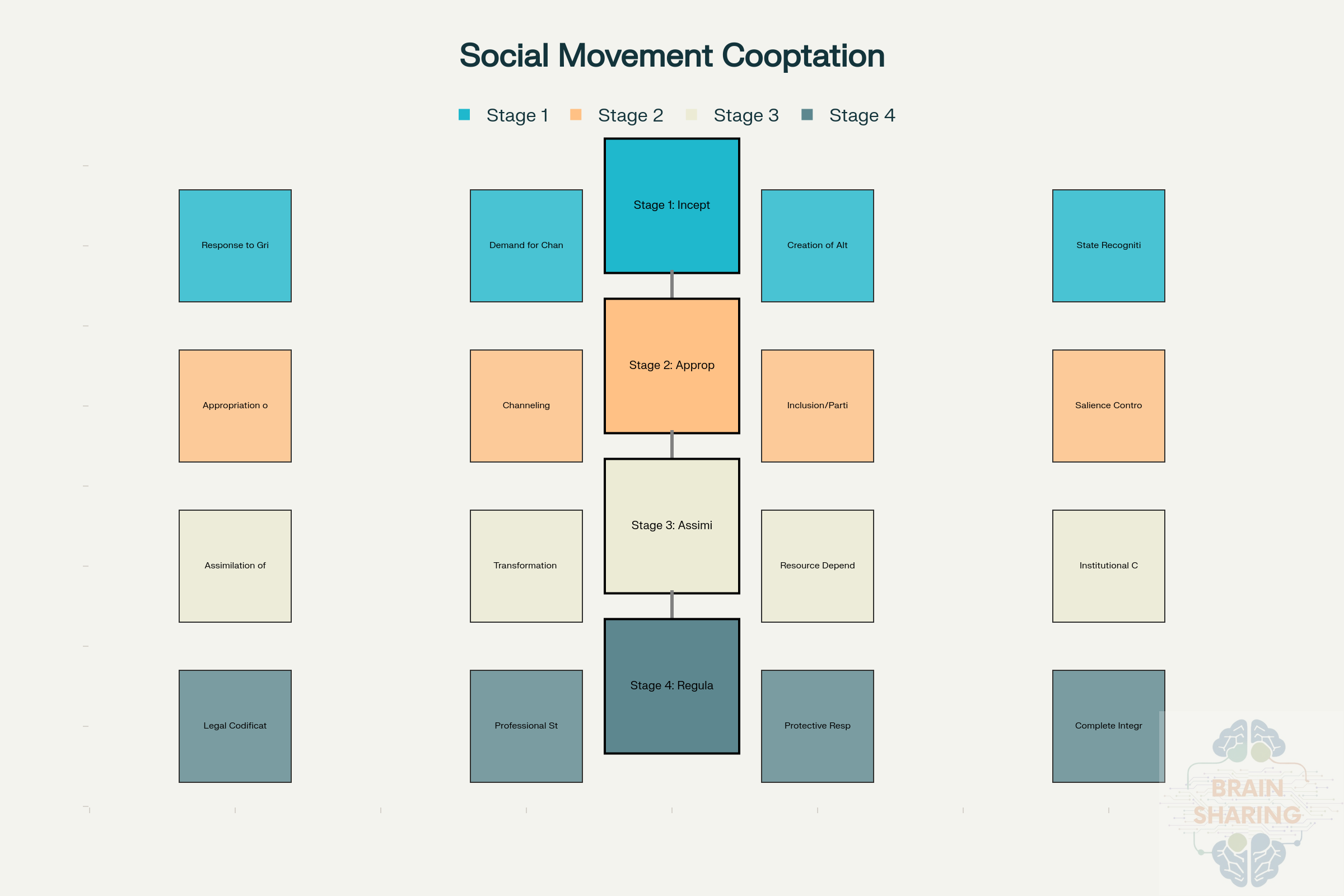

Research distills the assimilation of revolutionary movements into four key stages:

Inception: Revolutionary movements arise from widespread grievances, uniting communities around fundamental change. At this stage, authorities may grudgingly acknowledge the need for reform, recognizing the threat posed by organized dissent.

Appropriation: Authorities selectively adopt the language, tactics, and leaders of the movement—often stripping concepts of their transformative meaning. Movement representatives might be included in advisory roles, gaining influence but sacrificing autonomy.

Assimilation: Movement leaders are absorbed into formal structures, often through roles in government agencies or professional bodies. As seasoned leaders depart for stable, institutional positions, their organizations lose independence and vigor. Simultaneously, the movement’s programs are recast to align with bureaucratic priorities—efficiency, predictability, and narrow, measurable outcomes replace broader ambitions for systemic change.

Regulation: Authorities codify movement practices into law, enforcing professional standards and licensing requirements that exclude grassroots participation. This regulatory phase locks movement activities into rigid frameworks designed to serve institutional—rather than community—needs.

Historical and Contemporary Examples

The American labor movement’s transformation during the early-to-mid 20th century typifies this process. Initially a radical force advocating worker control and alternative social structures, labor’s gains were progressively institutionalized by legislation and partnership with state and corporate actors. Formal collective bargaining procedures, government oversight, and the expulsion of radical elements steered the movement from revolutionary origins to mainstream acceptance and stability.

The civil rights movement likewise transitioned from radical demands for economic and social transformation to more achievable, systemic reforms centered on legal equality. While key leaders entered advisory positions and incremental gains were codified into law, the movement’s original revolutionary critiques of capitalism and deep-seated racism were marginalized.

Even the environmental movement’s trajectory—from radical critiques of industrial society to professional organizations collaborating with government and industry—reflects how initial challenges can be diluted through cooptation and professionalization.

Mechanisms of Cooptation

Authorities use a range of sophisticated mechanisms to assimilate revolutionary movements:

Language and Discourse Appropriation: Movement vocabulary and concepts are adopted, repurposed, and emptied of their radical intent.

Resource Dependency: Movements become reliant on institutional funding that shapes their priorities and constrains advocacy.

Professional Integration: Leaders are incentivized to join formal structures where career opportunities and stability replace grassroots organizing.

Legal Regulation: Formal standards and licensing reserve movement practices for credentialed professionals, excluding volunteers and undermining grassroots character.

Implications and Resistance

This assimilation process highlights the resilience of dominant systems and the dynamic strategies required for genuine transformation. Movements seeking to maintain revolutionary potential must prioritize autonomous organizational structures, develop independent resource streams, and treat institutional engagement as tactical rather than defining. Resistance strategies—such as “conflictual cooperation” and building “countervailing power”—help movements engage with power structures without losing their core objectives.

Conclusion

The assimilation of revolutionary movements serves as a testament to the adaptability of power. Through intricate processes of cooptation, institutions disarm, reshape, and ultimately benefit from the energy and legitimacy once marshalled against them. Understanding this pattern is essential both for scholars and activists—revealing the double-edged sword of institutional engagement and the ongoing need for vigilance and innovation on the road to meaningful social change.

The Systematic Assimilation of Revolutionary Movements: How Authorities Transform Opposition into Integration

Revolutionary movements throughout history have emerged to challenge established power structures, demanding fundamental changes in social, political, and economic systems. However, a recurring pattern has emerged whereby authorities who initially opposed these movements eventually succeed in absorbing, neutralizing, or co-opting them into the very systems they once sought to overthrow. This phenomenon represents one of the most sophisticated forms of social control, transforming potential threats to the status quo into mechanisms that ultimately reinforce existing power structures.

Understanding Cooptation: Theoretical Foundations

The concept of cooptation was first systematically analyzed by sociologist Philip Selznick in his 1949 study of the Tennessee Valley Authority. Selznick defined cooptation as “the process of absorbing new elements into the leadership or policy-determining structure of an organization as a means of averting threats to its stability or existence”1. This foundational work established two key variables central to cooptation: power imbalances between challenging groups and established institutions, and the presence of threat that motivates institutional response1.

Building on Selznick’s work, scholars have identified cooptation as a complex process involving institutionalization, social control, and strategic policy changes1. Unlike direct suppression or violent confrontation, cooptation represents a more subtle approach where authorities absorb movement leaders, appropriate movement language and techniques, and gradually transform revolutionary goals into manageable reforms that pose no fundamental threat to existing power structures.

Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony provides another crucial theoretical lens for understanding this process. Gramsci argued that dominant classes maintain power not merely through force but through cultural and ideological leadership that secures consent from subordinate groups23. This “manufactured consent” operates through civil society institutions that shape ideas and beliefs, creating conditions where revolutionary movements may voluntarily participate in their own neutralization4.

The Four-Stage Model of Revolutionary Movement Assimilation

Research on community mediation and other social movements has revealed a systematic four-stage process through which authorities assimilate revolutionary movements1. This model demonstrates how what initially appears as isolated incidents of cooperation or compromise actually represents a comprehensive strategy of institutional absorption.

The Four-Stage Model of Social Movement Cooptation

Stage 1: Inception – The Birth of Challenge

The first stage begins when revolutionary movements emerge in response to shared grievances or unfulfilled needs within a population. These grievances are typically framed as fundamental injustices that demand systemic change1. The movement gains legitimacy by creating alternative institutions that demonstrate community support and signal serious intent to challenge existing power structures.

During this stage, authorities begin to perceive the need for policy adjustments or reforms. This recognition often stems from various motivations including genuine support for change, efficiency concerns, political expediency, or most critically, a desire to prevent more substantive challenges to their authority1. The presence of influential allies within targeted institutions becomes crucial, as these insider advocates help legitimize the movement’s concerns while simultaneously channeling them toward acceptable solutions.

1930s labor protest with workers holding signs demanding rights and better conditions during a large street demonstration wikipedia

Stage 2: Appropriation – Selective Absorption

The second stage involves two distinct but related processes of appropriation. First, authorities adopt the language and methods developed by the challenging movement, but strip them of their original revolutionary content1. This linguistic appropriation allows institutions to appear responsive to movement demands while fundamentally altering the meaning and application of movement innovations.

The appropriation of terminology often involves significant redefinition. For example, community mediation’s emphasis on voluntary participation and community empowerment was transformed into court-mandated processes focused on case disposal and administrative efficiency1. This redefinition benefits from the movement’s credibility while confusing public understanding of the original process.

The second aspect of appropriation involves the inclusion of movement representatives in policy-making bodies, advisory committees, and institutional oversight roles1. While this participation may yield incremental gains, it typically withholds substantive power while sharing administrative responsibilities. This creates what scholars term the “paradox of collaboration” – where continued access to decision-making processes becomes an end in itself, potentially superseding the movement’s original transformative goals1.

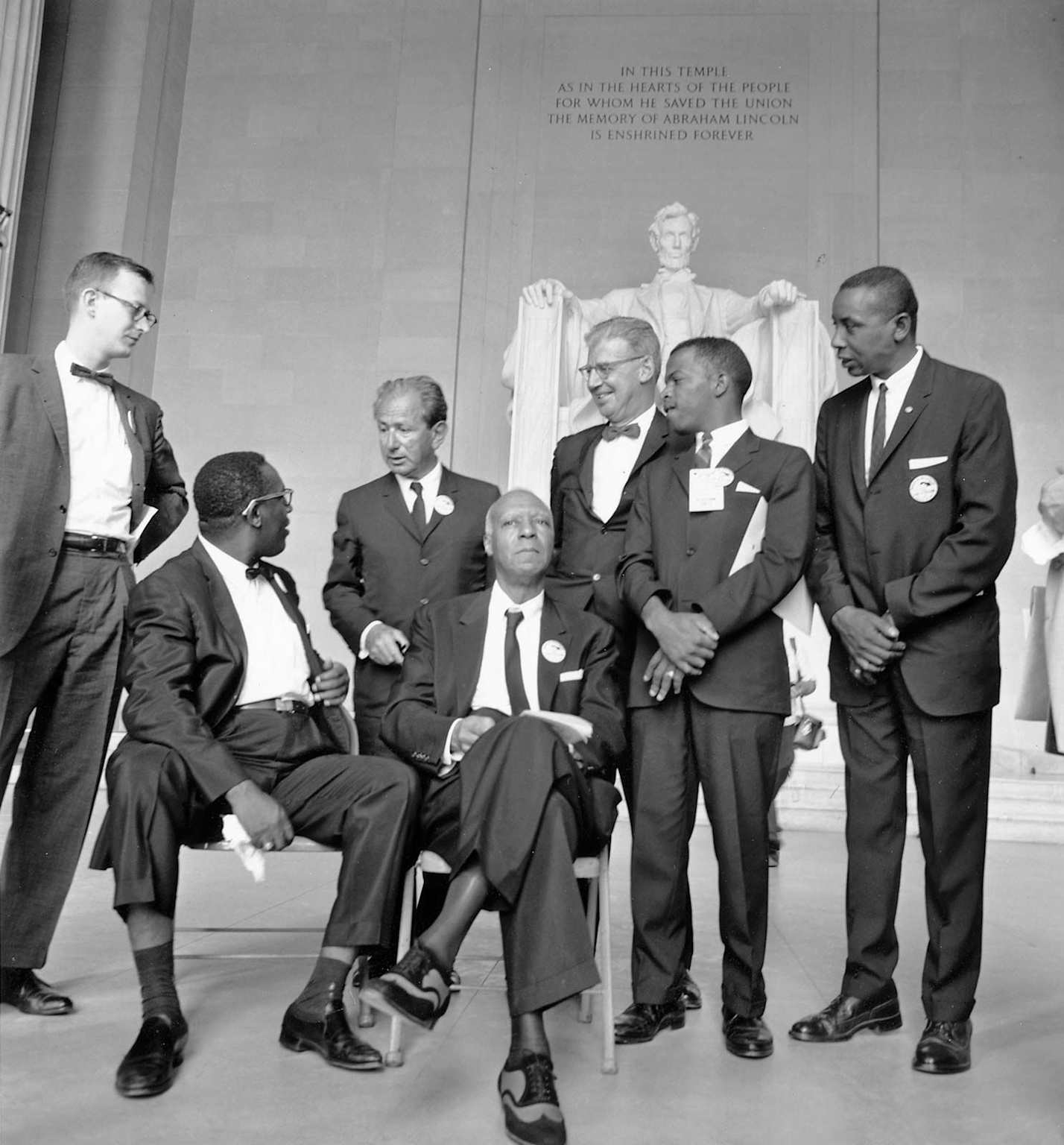

Civil rights leaders and government officials meet at the Lincoln Memorial, symbolizing the interaction between a revolutionary movement and authorities thoughtco

Stage 3: Assimilation – Institutional Capture

The third stage represents the most decisive phase of cooptation, where authorities absorb both movement leadership and organizational goals. This process operates through two primary mechanisms: the assimilation of movement leaders into institutional roles and the systematic transformation of program goals1.

Leadership assimilation occurs when authorities create formal positions within government agencies or affiliated organizations that attract experienced movement leaders. These positions often offer more stable funding and professional advancement opportunities than movement organizations can provide1. The departure of seasoned leaders creates significant capacity gaps within the movement, weakening its ability to maintain independent organizing and strategic vision.

Simultaneously, governmental offices established to coordinate or support movement activities frequently evolve into regulatory agencies that prescribe policies, guidelines, and operational standards1. These agencies systematically transform traditional movement goals – such as community empowerment, democratic participation, and systemic change – into bureaucratic metrics focused on efficiency, standardization, and measurable outcomes that align with institutional priorities.

The Big Six organizers of the Civil Rights Movement, including Martin Luther King Jr., at a formal meeting in the 1960s thoughtco

Stage 4: Regulation – Formal Codification

The final stage involves the formal legal codification of movement practices and values. While this may appear to represent movement success, regulation often comes with restrictions that fundamentally alter movement practices and impose professionalization requirements that conflict with original principles1. The increasing regulation leads to what scholars term the “legalization” of movement practices, making them more rigid and controlled by formal institutional systems.

This regulatory framework typically includes ethics codes, professional standards, and licensing requirements that exclude community volunteers and grassroots practitioners who formed the movement’s original base1. The movement’s practices become standardized according to institutional rather than community needs, completing the transformation from revolutionary challenge to institutional support mechanism.

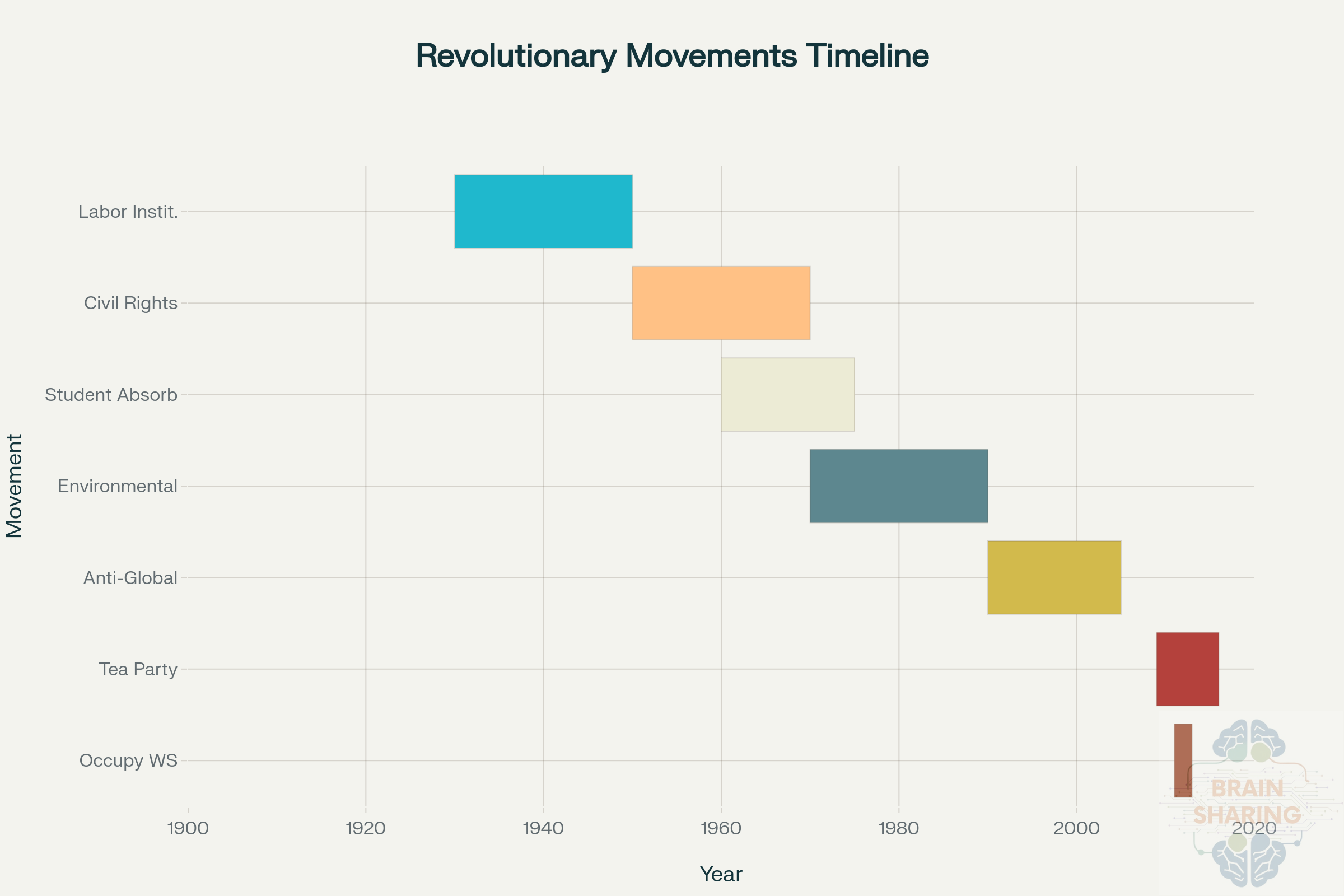

Timeline of Revolutionary Movement Cooptation in the 20th and 21st Centuries

Historical Examples of Movement Assimilation

The pattern of revolutionary movement assimilation has been replicated across diverse social movements throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, demonstrating the systematic nature of this process.

Labor Movement Institutionalization (1930s-1950s)

The American labor movement provides perhaps the most comprehensive example of revolutionary movement assimilation. Initially emerging as a radical challenge to industrial capitalism, the labor movement established alternative institutions including worker cooperatives, independent unions, and socialist political organizations56. The movement’s early demands included worker control of production, fundamental restructuring of economic relationships, and the creation of alternative economic systems.

However, the post-World War II period witnessed systematic institutionalization of labor organizing. The Wagner Act of 1935, while granting collective bargaining rights, channeled labor organizing into legally regulated processes that limited the scope of acceptable demands5. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 further restricted labor organizing while forcing communist and radical elements out of the movement7. This legal framework transformed labor organizing from a revolutionary challenge to capitalism into a mechanism for negotiating worker benefits within existing economic structures.

Group of 1930s industrial workers united, symbolizing the rise of labor movements and union solidarity themilitant

The institutionalization process was completed through the incorporation of labor leaders into government advisory roles, the establishment of formal collective bargaining processes, and the creation of professional labor relations expertise that separated union leadership from rank-and-file organizing58. By the 1950s, labor organizing had evolved from revolutionary challenge to institutional support for industrial capitalism, with union leaders becoming partners in maintaining workplace stability and economic growth.

Civil Rights Movement Integration (1950s-1970s)

The civil rights movement demonstrates how revolutionary demands for fundamental social transformation can be channeled into incremental reforms that preserve essential power structures while appearing to address movement grievances910. The movement initially challenged not only legal segregation but the entire system of racial capitalism that structured American society.

However, the movement’s institutionalization involved the selective incorporation of moderate leaders into government advisory roles, the channeling of movement demands into legal and legislative processes, and the systematic marginalization of more radical elements that challenged economic structures9. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, while significant achievements, represented the transformation of revolutionary demands for economic justice and structural change into legal reforms that maintained fundamental economic relationships.

The process of assimilation was evident in the different treatment of moderate leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., who were eventually incorporated into mainstream political discourse, versus more radical figures like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers, who faced systematic suppression1112. The movement’s original demands for economic justice and systemic change were gradually replaced with goals of legal equality and political inclusion that posed no fundamental threat to existing power structures.

Civil rights leaders and government officials meet at the Lincoln Memorial, symbolizing dialogue between revolutionary movements and authorities in the 1960s britannica

Environmental Movement Mainstreaming (1970s-1990s)

The environmental movement’s assimilation illustrates how revolutionary ecological consciousness can be transformed into manageable policy reforms that actually strengthen existing economic systems1314. The movement initially emerged with radical critiques of industrial capitalism, consumerism, and the fundamental relationship between human society and natural systems.

However, the movement’s institutionalization involved the creation of large environmental organizations that relied on professional staff and foundation funding rather than grassroots organizing13. These organizations developed close relationships with government agencies and corporate interests, leading to the promotion of market-based solutions and technological fixes that preserved fundamental economic structures while addressing environmental concerns through regulation and efficiency measures.

The transformation was particularly evident in the shift from environmental justice organizing in communities of color to mainstream environmentalism focused on wilderness preservation and species protection13. This shift effectively separated environmental concerns from social justice issues, allowing authorities to address environmental problems without challenging the economic and social systems that created them.

Activists holding a banner demanding systemic change to address climate change, highlighting grassroots environmental protest wikipedia

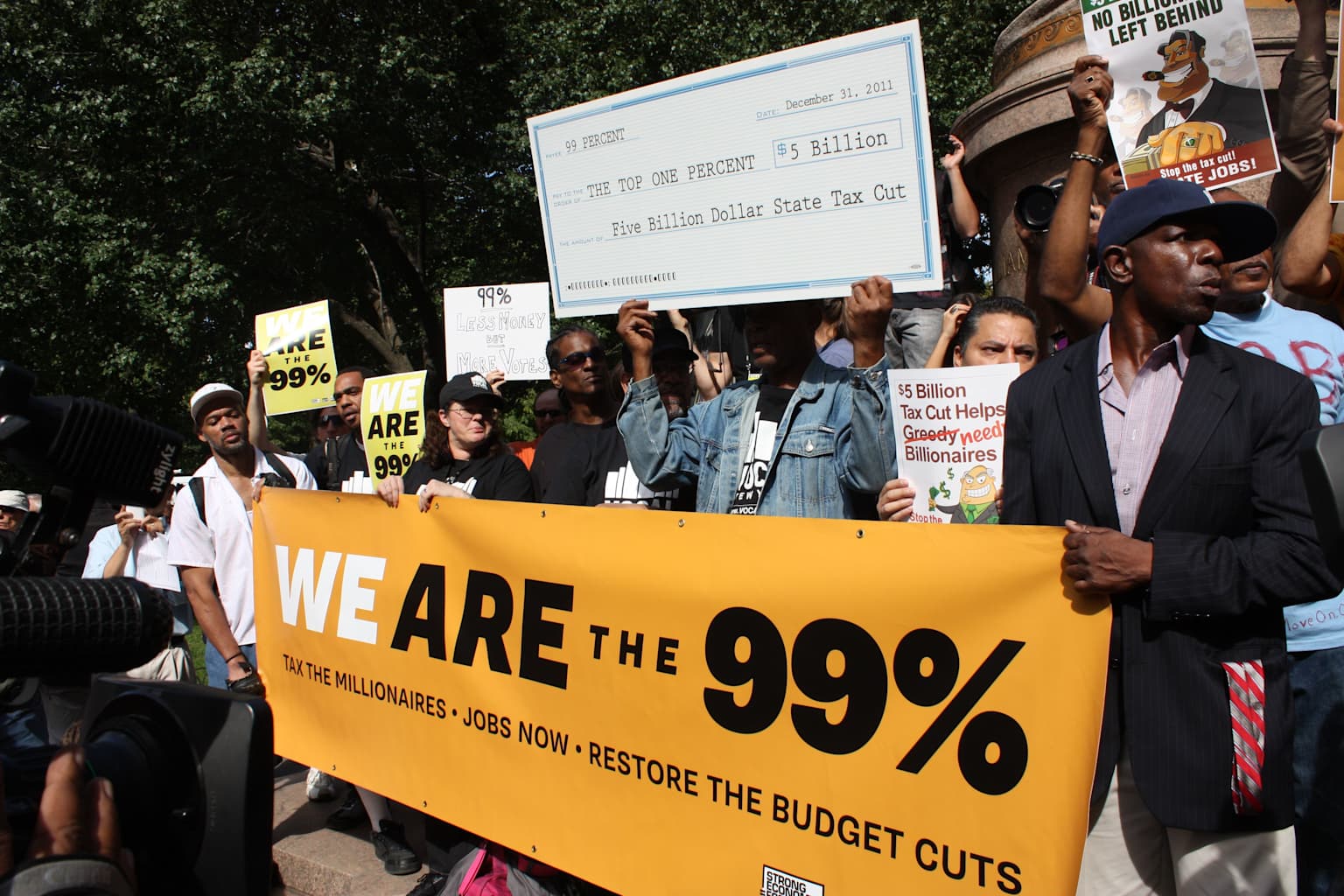

Contemporary Examples: Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street

More recent examples demonstrate the continued relevance of this assimilation process. The Tea Party movement, initially emerging as a grassroots challenge to government spending and corporate influence, was rapidly incorporated into Republican Party politics through the support of well-funded organizations like Americans for Prosperity1516. The movement’s anti-establishment rhetoric was channeled into support for pro-business policies that strengthened rather than challenged corporate power.

Conversely, the Occupy Wall Street movement illustrates what happens when revolutionary movements resist institutionalization. Despite generating significant public attention and shifting national discourse about economic inequality, the movement’s refusal to develop formal leadership structures or engage in traditional political processes limited its ability to achieve concrete policy changes171819. The movement’s dissolution demonstrates both the challenges of maintaining revolutionary independence and the effectiveness of institutional assimilation in neutralizing potential threats.

Occupy Wall Street protesters holding signs and banners advocating economic equality and opposing tax cuts for the wealthy cnn

Mechanisms and Strategies of Cooptation

The systematic nature of movement assimilation involves multiple interconnected mechanisms that operate simultaneously across different aspects of movement organization and activity20.

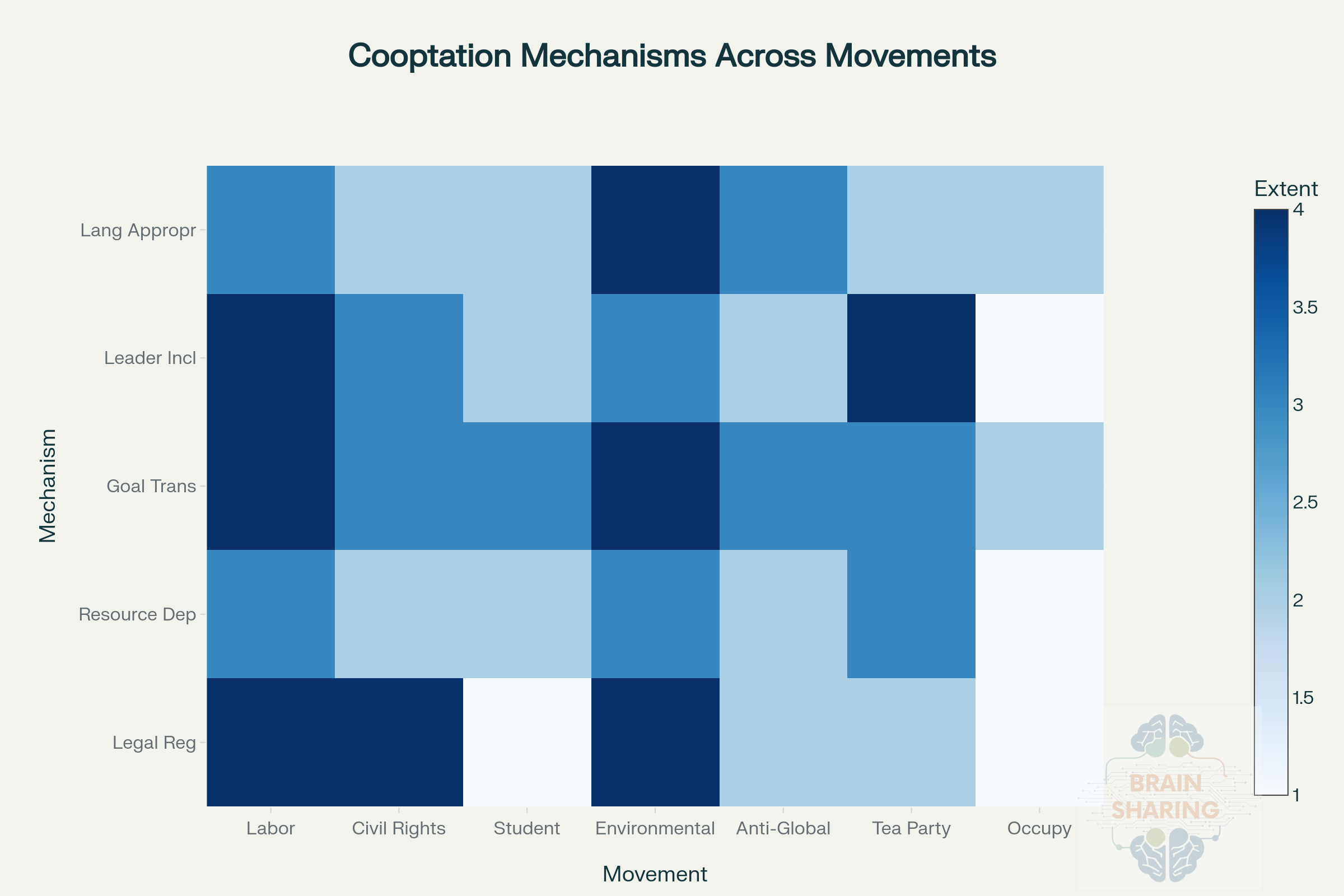

Cooptation Mechanisms Across Different Social Movements

Language and Discourse Appropriation

One of the most subtle yet effective mechanisms involves the appropriation of movement language and concepts while fundamentally altering their meaning and application1. Authorities adopt movement terminology but redefine it according to institutional priorities. For example, concepts like “empowerment,” “participation,” and “community control” are incorporated into government programs but transformed to mean consultation, advisory roles, and managed involvement rather than genuine democratic control.

This linguistic appropriation serves multiple functions: it allows institutions to appear responsive to movement demands, confuses public understanding of original movement goals, and provides legitimacy for institutional programs that may actually undermine movement objectives1. The appropriation of language is particularly effective because it maintains the appearance of supporting movement goals while fundamentally altering their implementation.

Resource Dependency and Funding Control

The creation of funding streams that support movement activities while imposing restrictions on their use represents another crucial mechanism of cooptation211. Government grants, foundation funding, and corporate sponsorship often come with requirements that limit advocacy activities, constrain organizational autonomy, and redirect movement energy toward service provision rather than systemic change.

This resource dependency creates what scholars term “nonprofit industrial complex” – a system where movement organizations become dependent on funding sources that have interests in maintaining existing power structures21. Organizations gradually adapt their programs and messaging to align with funder priorities, leading to the transformation of movement goals without explicit pressure or coercion.

Professional Integration and Career Pathways

The creation of professional career pathways that attract movement leaders into institutional roles represents a systematic mechanism for draining movements of experienced leadership1. These positions often offer better compensation, job security, and professional advancement than movement organizations can provide, creating powerful incentives for individual leaders to transition from organizing to administration.

This professional integration serves multiple functions: it removes experienced leaders from movement organizations, provides institutions with individuals who understand movement dynamics and can help manage potential challenges, and creates a class of former movement leaders who have institutional interests in maintaining existing systems1.

Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

The development of legal and regulatory frameworks that codify movement practices while imposing restrictions on their implementation represents the culmination of the cooptation process1. These frameworks typically include licensing requirements, professional standards, and ethical codes that exclude community volunteers and grassroots practitioners while privileging professional expertise and institutional credentials.

Legal regulation transforms movement practices from community-controlled activities into professionally administered services, completing the shift from revolutionary challenge to institutional support mechanism1. The regulatory framework ensures that movement innovations serve institutional rather than community needs, effectively neutralizing their transformative potential.

Theoretical Implications and Resistance Strategies

The systematic nature of movement assimilation reveals important theoretical insights about power, resistance, and social change. The process demonstrates that authorities have developed sophisticated mechanisms for neutralizing challenges that go far beyond direct suppression or co-optation of individual leaders.

Gramsci’s Hegemony and Consent Manufacturing

The assimilation process exemplifies Gramsci’s concept of hegemony – the way dominant classes maintain power through cultural and ideological leadership that secures consent from subordinate groups234. Rather than simply suppressing revolutionary movements, authorities create conditions where movement leaders voluntarily participate in their own neutralization by accepting institutional roles and modified goals that serve existing power structures.

This manufactured consent operates through what Gramsci termed “civil society” – the network of institutions, organizations, and cultural practices that shape consciousness and create common sense understandings of social reality4. The assimilation process transforms revolutionary movements into components of civil society that help maintain rather than challenge existing power relations.

Systems Theory and Functional Integration

From a systems theory perspective, the assimilation process represents the way complex social systems maintain stability by integrating challenges into existing structures rather than suppressing them2223. Revolutionary movements are treated as functional components that help the system adapt to changing conditions while maintaining essential power relationships.

This perspective suggests that the assimilation process is not necessarily the result of conscious planning by authorities but rather represents the systematic tendency of complex social systems to neutralize potential threats through integration rather than confrontation23. The process operates through multiple feedback mechanisms that gradually transform revolutionary challenges into system-supporting functions.

Strategies for Maintaining Revolutionary Potential

Despite the systematic nature of cooptation, research has identified several strategies that movements can employ to maintain their revolutionary potential while engaging with institutional processes21910:

Autonomous Organization Building: Movements can maintain independent organizational structures that operate outside institutional control, providing space for developing radical critiques and alternative visions21. These autonomous spaces allow movements to engage with institutions tactically while maintaining strategic independence.

Conflictual Cooperation: Rather than choosing between confrontation and cooperation, movements can employ “conflictual cooperation” – engaging with institutions when it serves movement goals while maintaining the capacity for confrontation when necessary21. This approach requires sophisticated political analysis and strong internal organization.

Countervailing Power: Movements can develop “countervailing power” – organizational resources and political capabilities that allow them to resist cooptation efforts while engaging in institutional processes21. This requires building independent resource bases and maintaining strong connections to grassroots constituencies.

Learning and Adaptation: Movements can treat institutional engagement as a learning process that develops new skills and capabilities while maintaining commitment to transformative goals21. This approach emphasizes the development of “deliberative skills” that allow movement representatives to navigate institutional processes without being captured by them.

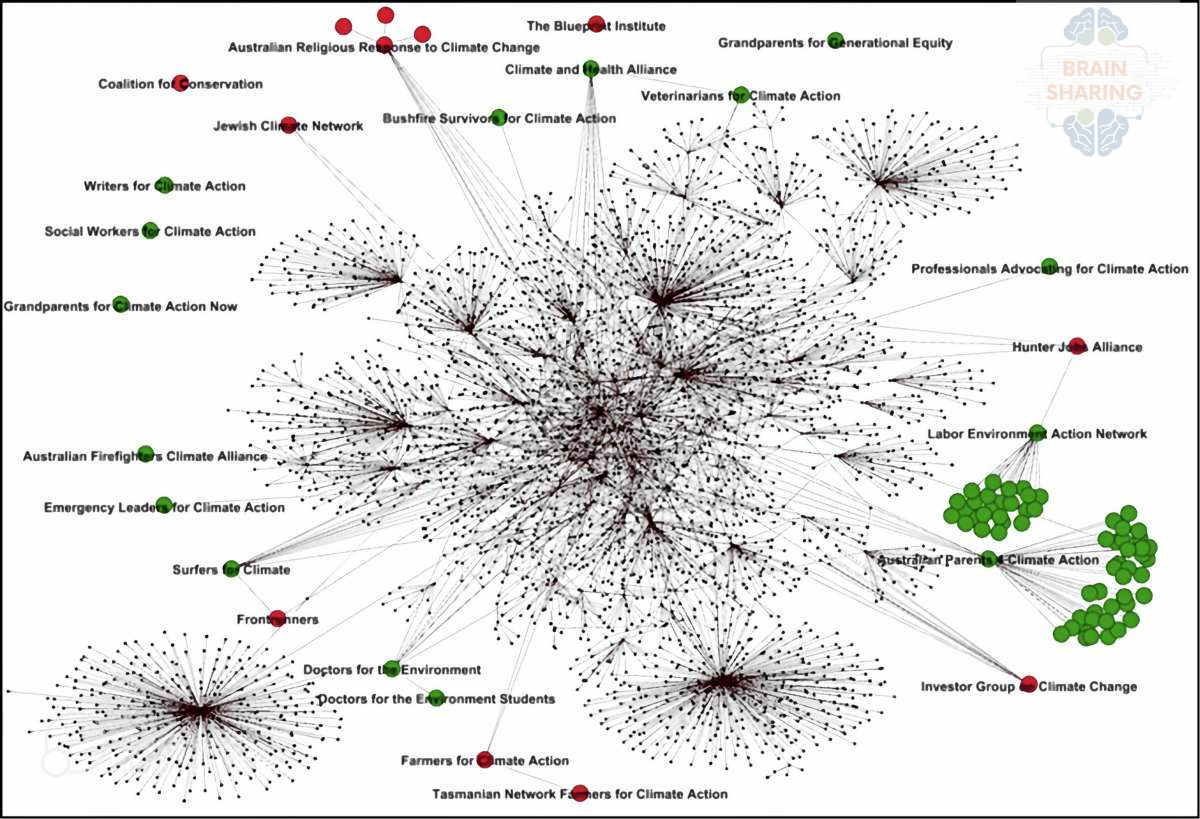

Network graph of climate action groups showing their interconnections and assimilation into broader activist networks nature

Contemporary Relevance and Future Implications

The systematic assimilation of revolutionary movements remains highly relevant in contemporary political contexts, where movements continue to emerge challenging existing power structures while facing sophisticated strategies of institutional absorption.

Digital Age Cooptation

Contemporary movements face new forms of cooptation related to digital technology and social media platforms. Tech companies and government agencies have developed sophisticated capabilities for monitoring, influencing, and channeling online organizing activities24. The platformization of social movements creates new dependencies on corporate-controlled communication systems that can be manipulated to serve institutional rather than movement interests.

The rise of “digital activism” often channels movement energy into online activities that feel meaningful to participants but have limited impact on actual power structures24. This represents a new form of cooptation where authorities don’t need to suppress or absorb movements – they can simply ensure that movement activities remain within digital spaces that pose no real threat to existing institutions.

Neoliberal Cooptation Strategies

The neoliberal period has seen the development of new cooptation strategies that emphasize market-based solutions and public-private partnerships1325. Environmental movements, for example, have been channeled into support for carbon markets and corporate sustainability initiatives that provide legitimacy for continued economic growth while addressing environmental concerns through market mechanisms.

This neoliberal cooptation is particularly sophisticated because it incorporates movement concerns into market-based solutions that actually strengthen rather than challenge existing economic structures13. Movements find themselves supporting policies that appear to address their concerns while actually reinforcing the systems they originally sought to transform.

Global Resistance Networks

Contemporary movements have also developed new strategies for resisting cooptation through global networking and solidarity2625. The anti-globalization movement, for example, created international networks that were more difficult for any single authority to co-opt or control26. However, these networks also face new challenges related to coordination, resource distribution, and maintaining coherent political vision across diverse contexts.

The development of “alter-globalization” movements represents an attempt to move beyond purely oppositional politics toward the construction of alternative systems25. However, these efforts also face cooptation pressures as authorities develop new strategies for channeling alternative visions into manageable reforms.

Conclusion

The systematic assimilation of revolutionary movements represents one of the most sophisticated forms of social control developed by modern authorities. Rather than simply suppressing challenges to existing power structures, this process transforms revolutionary movements into mechanisms that ultimately reinforce the very systems they originally sought to overthrow.

The four-stage model of cooptation – inception, appropriation, assimilation, and regulation – provides a framework for understanding how this process operates across different historical contexts and movement types. From the labor movement of the 1930s to contemporary environmental and social justice movements, the pattern remains remarkably consistent: initial opposition gives way to selective incorporation, which leads to institutional absorption and finally to formal regulation that completes the transformation from revolutionary challenge to system support.

Understanding this process is crucial for contemporary movements seeking to create fundamental social change. The research demonstrates that institutional engagement, while potentially necessary for achieving concrete gains, carries inherent risks of cooptation that require sophisticated organizational strategies and political analysis to navigate successfully.

The most effective resistance strategies appear to involve maintaining autonomous organizational structures while engaging institutions tactically, developing countervailing power that provides alternatives to institutional resources, and treating institutional engagement as a learning process that builds movement capacity rather than replacing movement goals.

Ultimately, the systematic nature of movement assimilation reveals the resilience and adaptability of existing power structures while also highlighting the continued importance of revolutionary organizing for creating fundamental social change. As authorities develop increasingly sophisticated cooptation strategies, movements must develop equally sophisticated resistance strategies that maintain transformative vision while engaging pragmatically with institutional realities.

The ongoing relevance of this analysis is evident in contemporary movements from Black Lives Matter to climate justice organizing, which continue to face similar pressures toward institutionalization and cooptation. Understanding the historical patterns and theoretical dynamics of movement assimilation provides essential knowledge for those committed to creating the fundamental social transformations that our current crises demand.

HOME

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-co-optation-does-have-do-roe-v-wade-michael-robinson-byrd

https://bretterblog.wordpress.com/2016/09/07/institutionalization-as-social-movement/

https://in.boell.org/en/2009/05/29/left-left-link-between-revolutionary-and-mainstream-politics

https://library.law.howard.edu/civilrightshistory/indigenous/allotment

https://phys.org/news/2020-10-rebel-groups-moderate-gaining-political.html

https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-pdf/134/659/1019/57025867/uead094.pdf

https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1828939

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14742837.2019.1577133

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/radical-movements-and-political-power/

https://undergradjournal.history.ucsb.edu/spring-2022/rodriguez/

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/a133b977-9dfb-4fc9-baee-633030f2b2d8/content

https://www.npr.org/2022/04/01/1089990539/climate-change-politics

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/1f2e3425-b7eb-4799-b7c7-c0beca0fe789/content

https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/cooptation-in-social-movements

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?dswid=-8594&pid=diva2%3A1318737

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0959680103009001453?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1318737/FULLTEXT01.pdf

https://sociology.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/faculty/voss/Voss%20and%20Sherman.pdf

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14742837.2019.1577133

https://www.scielo.br/j/bpsr/a/mbLWZ6T93bJ6dLR5QQQBVDg/?lang=en

https://www.e-ir.info/2007/12/22/assess-the-impact-of-feminist-thought-on-contemporary-politics/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Students_for_a_Democratic_Society

https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=ughonors

https://duepublico2.uni-due.de/receive/duepublico_mods_00076217

https://harvardpolitics.com/rise-of-the-mainstream-feminist/

https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-student-movement-of-the-1960s.html

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?psid=3337&smtid=2

https://www.lhistoire.fr/english-version/the-history-and-politics-of-the-black-panther-party

https://library.fes.de/libalt/journals/swetsfulltext/12558892.pdf

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook_print.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3337

https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/allg_Texte/Gramscian_Constellations.pdf

https://www.leftvoice.org/gramsci-s-three-moments-of-hegemony/

https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0104656

https://pure.au.dk/portal/en/publications/social-movements-and-sociological-systems-theory

https://www.powercube.net/other-forms-of-power/gramsci-and-hegemony/

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/power-elite

https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/4046/1/Jaworiwsky_Alexandra_2023_MDES_SFI_MRP.pdf

https://www.counterfire.org/article/gramsci-the-revolutionary-in-his-own-words/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/integration-theories-tariro-sakala–tlzof

http://www.isguc.org/?p=article&id=187&cilt=6&sayi=1&yil=2004

https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/governance-crone-fuchs-2006c.pdf

https://www.rosalux.de/en/news/id/46700/a-brief-history-of-the-alter-globalization-movement

https://www.businessinsider.com/occupy-wall-street-income-inequality-ten-years-later

https://www.wildcat-www.de/dossiers/forcesoflabor/Labor_Movements_and_Capital_Migration_1984.pdf

https://truthout.org/articles/after-six-months-a-look-at-what-occupy-wall-street-has-accomplished/

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3382

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/anti-globalization-movement

https://time.com/archive/7101574/occupy-wall-street-one-year-later-did-it-make-a-difference/

https://www3.gmu.edu/programs/icar/ijps/vol9_1/Eschle_91IJPS.pdf

https://www.e-ir.info/2013/11/28/assessing-the-impact-of-the-tea-party-on-the-republican-party/