How the Existential Threat of Cryptocurrency Exposes Power, Trust, and the Battle Over Financial Control

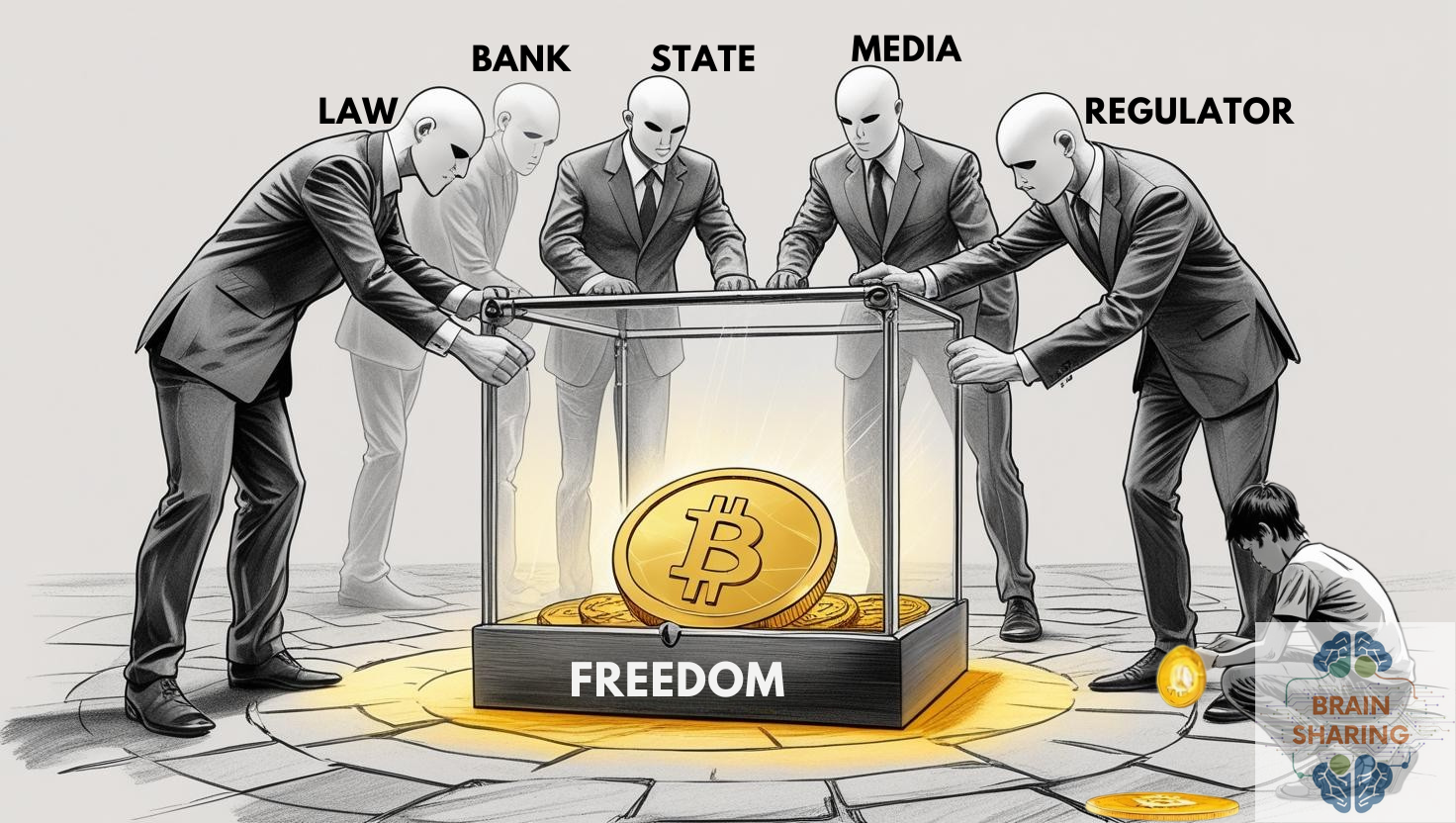

Cryptocurrency arrived not just as a technological innovation, but as a litmus test for the world’s trust in its institutions. The intense reaction—from nervous governments and central banks to skeptical economists and alarmist headlines—was never merely about code or market volatility. Instead, the underlying fear was the challenge crypto posed to accumulated power: its capacity to route around gatekeepers, decentralize money creation, and empower individuals outside existing legal and political frameworks. The rise of peer-to-peer digital currency put core functions of state and financial intermediaries on trial, spotlighting the fragility of their supposed monopolies and raising uneasy questions about legitimacy and authority.

While regulators and media obsessed over narratives of crime and volatility, they often echoed the legacy system’s own scandals and failures, revealing that the real threat was not new chaos but the exposure of old, unresolved rot.

The strongest legal crackdowns today fall on tools offering true privacy, anonymity, and permissionlessness—attributes incompatible with systems reliant on total visibility and regulatory veto. Suppression of low-adoption privacy networks like Monero or DeFi platforms signals insecurity, not strength. Young generations, already wary of inherited systems, now have tools to bypass them outright. To those with a stake in maintaining order, any technology that offers autonomy also risks disobedience. The resulting convergence of regulation, suppression, and co-optation—evident in global efforts to domesticate crypto through central bank digital currencies and sweeping compliance regimes—proves that crypto’s power lies in its ability to redistribute control, not just capital. In the end, crypto acts as both a mirror and a stress test, exposing a system less stable than it claims, and confirming that the more power crypto threatens, the more urgent and pervasive the response will be.

#Hashtags

#CryptoDebate #FinancialSovereignty #Regulation #Decentralization #TrustCrisis #PowerAndMoney #PrivacyTech #SystemicRisk #BankingReform #DigitalAutonomy

From the moment Bitcoin burst into public consciousness, cryptocurrency has been enveloped in an aura of disruption, both celebrated and condemned, but never ignored. The peculiar thing is this: the question of why crypto was perceived as a threat is not simply a matter of technology or market volatility. The origins of this alarm reveal much about power, trust, and the anxieties of an age where old certainties are in flux, and new instruments of autonomy are rising quicker than the law can keep pace.

When the first alarms sounded, it was not only the technical crowd listening. Governments and central banks, arbiters of the world’s monetary reality, sensed a disturbance in their usual dominion. Here was a system of value exchange that paid no deference to borders, legacy rules, or the traditional monopoly on money creation. Economists, too, offered warnings, some out of prudence and others out of a deep skepticism toward outsiders re-engineering finance without credentials or oversight. The reaction from media outlets swirled these voices together, amplifying fearful speculation with tales of digital pirates and economic chaos12.

For those at the helm of existing systems of power, the very existence of a parallel financial universe—one that could operate peer-to-peer, without permission, and outside the orbit of KYC, AML, or capital controls—called the existing order into question. What would happen if individuals en masse chose to route around central banks, tax authorities, and intermediaries entirely? Was this not, in essence, a challenge not just to money, but to the rationale behind political and legal oversight itself34?

More than a threat to process, crypto’s core architecture is inherently adversarial to concentrations of power that mark the modern world. Central banks’ ability to print currency at will—a privilege woven into the fabric of modern economics—finds its first systematic challenger in code that enforces monetary policy through decentralized consensus and fixed supply56. The prospect that people might “opt out” of national currencies, or move capital without oversight, is an existential specter for states whose regulatory muscle depends on a controlled flow of money. And to the institutions—banks, brokers, legacy payment processors—that have long stood as the choke-points and toll-collectors of finance, a world of permissionless value transfer looks less like innovation than like obsolescence14.

What is even more fascinating is that the commotion surrounding crypto was never really about its technical magic. If it had simply been about cryptographic signatures or distributed ledgers, central banks and wealth managers would have had little cause for hand-wringing.

But the real disruptive spark was autonomy: the ability to transact and organize outside the gates, without needing to ask for approval—an affront to every structure built on mandatory gatekeeping.

When those same technologies are absorbed by the establishment—think central bank digital currencies or open ledgers deployed by megabanks—there is no comparable panic, only cautious optimism. Why? Because replicas of the tool are not the threat; it’s losing oversight—permissionless-ness—that strikes fear in the heart of the status quo765.

And so began the world’s fascination with the narrative of crypto as synonymous with crime and shadowy dealings. Over and again, headlines splashed stories of Silk Road or terrorist fundraising, and news anchors speculated whether the next financial crisis would originate in an unregulated, unpredictable market.

What went unspoken, or at least unhighlighted, was the plain truth: a tiny fraction of global illicit transactions occur in the crypto sphere compared to the vast oceans of fiat dark money sloshing through the world’s major banks8910. The media, however, did not amplify the failures of institutional finance—the repeated bank bailouts, scandalized money-laundering, or routine gaming of the system by established players—in quite the same breathless tone.

For many, it was a classic case of moral panic: the focus was not just on the actual risks, but on the need to sustain legitimacy by othering the new and defending the old112.

That brings us to the present, where legal panic often attaches itself most keenly to the protocols and tools that seem the hardest to domesticate. Coins like Monero and protocols such as Tornado Cash evoke disproportionate reaction not because they are widely used or pose outsized economic danger, but precisely because they prove—in small, concrete ways—that true sovereignty and privacy in finance remain possible. Even as adoption remains modest, the idea that untraceable or uncensorable value transfer is more than theoretical unsettles regulatory systems built on absolute visibility and veto power1213. Thus, even beyond their proportions, such systems are pre-emptively suppressed, delisted, or outright banned, not because they have caused catastrophe, but because their existence is deemed incompatible with the prevailing order.

It’s not just about criminality, then—it’s about control. The greatest discomfort underlying regulatory action isn’t merely that users might break the law, but that these systems enable them to say no to rules they never voted for in the first place. If DeFi offers genuine alternatives to banks, and “unhosted” wallets can store value immune to arbitrary seizure, then power is forced to reckon with a class of citizens who are participants, not supplicants2714. What happens when entire generations, already skeptical of legacy institutions, are equipped with the tools to bypass the traditional choke points of economic life?

It is not the number of crypto holders that worries establishment thinkers, but the cultural precedent: youth dissatisfied with inherited systems no longer have to protest at the gates—they can simply build their own markets, their own rules, their own tools4157.

This is where the question transforms: can any technology truly be “safe” in the eyes of power, once it gives users not just convenience, but genuine autonomy—and yes, the means to disobey? Safety, in this light, shifts from encompassing user or consumer welfare to the stability of the system. The logic of enforcement is not to make things truly secure, but to ensure that tools cannot be reliably wielded against their creators1312. If financial sovereignty becomes more than rhetoric, the traditional equations of leverage and obedience are rewritten. Regulatory and institutional instinct, therefore, is not simply to ban what is “harmful,” but to make disobedience impractical or unacceptably risky; “safety” is redefined as compliance1216.

Through all of this, cryptocurrency serves as a kind of mirror—reflecting both the vulnerabilities and ambitions of the system that seeks to contain it. The intensity of the reaction, the rush to regulate and suppress, tells its own story: crypto did not invent distrust in banks, nor did it invent state overreach, but it made previously invisible cracks explicit17215.

When bank bailouts are normalized as regrettable but necessary, while the same magnitude of scrutiny is never applied to small-scale crypto scandals, one sees the performative element of the established narrative—a performance that stands most exposed whenever legacy actors quietly adopt the very instruments they once denounced.

What, in the end, is really being protected? Again, it is essential to scrutinize the difference between preaching stability and enacting it. Time and again, regulatory action is justified in the name of system stability, yet “stability” is often an achievement of messaging as much as policy. Cryptocurrency underscores a reality financial institutions have long masked with prestige and process: a system only looks stable so long as there is no credible alternative. When alternatives arise, and when gatekeepers respond with suppressive zeal, one must ask whether it is stability or simply the stability of the current gatekeepers that is being preserved61819.

Security, too, is rebranded in light of such developments. The rhetoric of investor protection and market integrity is indispensable to the structures that govern fiat economies the world over, but it is all too easily conflated with the less virtuous aim of monopoly over enforcement.

The ability to surveil, confiscate, and dictate the flow of capital is as much about economic management as it is about retaining unique powers and privileges.

Crypto challenges not only the mechanism but the moral claim to such powers. It is perhaps no surprise then, that the vocabulary of crime—always potent in shaping public opinion—is so thoroughly deployed to delegitimize what cannot be corralled through softer means20321.

All this leads to a final, inescapable conclusion. If crypto were not a threat—if it posed no real avenue for disobedience or escape from the prevailing economic script—the world’s regulators, lobbyists, and policymakers would have left it to wither or thrive in obscurity. But as regulation, suppression, infiltration, and ultimately co-optation have expanded, the underlying diagnosis is hard to avoid: the depth and breadth of institutional anxiety correspond directly to crypto’s ability to redistribute power away from incumbents. New forms of money, new forms of organization, new vehicles for dissent—these are not simple novelties, but cracks in the edifice that previous generations accepted as immovable. Even cautious adoption of crypto-derivative tools, like CBDCs, is itself an admission: if you cannot beat autonomy, seek to domesticate it, to channel it back into orthodox frameworks, where every transaction can again be monitored and made subject to permission657.

Crypto’s story is, ultimately, the latest installment in the age-old saga of control, autonomy, legitimacy, and fear. Its legacy, whether as a tool, a threat, or a mirror, is yet to be settled. But in its short life, it has illuminated the fault lines of a system deeply invested in the status quo, while equipping a new generation to imagine—and, if they wish, enact—something different.

Citations List

11 J. Young and S. Cohen, “Introduction: The Moral Panic Concept” (2013).

20 “Are crypto-assets a threat to financial stability?,” Deutsche Bundesbank (2023).

1 “How Crypto and Blockchain Challenge Centralized Power,” The Street (2023).

2 K. Coulter, “The Media Life of Cryptocurrencies,” University of Essex Ph.D. thesis (2022).

3 “A great disturbance in the crypto: Understanding cryptocurrency…,” ScienceDirect.

4 Punzano, “The Rise of Decentralized Power: State Nations, Cryptocurrencies, and Corporations in the Age of Blockchain” (2024).

8 K. Coulter, “Microsoft Word – FinalCorrectionCopy_KellyCoulter_PhDthesis_080922 copy.docx,” University of Essex (2022).

17 “Exploring the Disruptiveness of Cryptocurrencies: A Causal Layered…,” PMC (2020).

15 “Going mainstream: Cryptocurrency narratives in newspapers,” ScienceDirect.

7 “The geopolitics of Bitcoin: Exploring the implications for global…,” Cointelegraph (2024).

10 A.K. Brown, “The Criminal Side of Cryptocurrency” (2023).

9 K. Doucette et al., “Behind the Headlines: Debunking Misconceptions of Cryptocurrency and Crime,” Wilson Center (2025).

12 “DeFi Privacy Under Threat: KYC, Blacklists, and Censorship,” ICO Holder (2025).

6 “Cryptocurrencies And Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCS): Implications For Monetary Policy And Financial Stability,” SSRN (2025).

21 J. Collins, “Crypto, crime and control” (2022).

13 Audrey Nesbitt, “Can DeFi Achieve Compliant Privacy Without Sacrificing Its Decentralized Soul?” HackerNoon (2025).

5 “Cryptocurrencies and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Implications for Monetary Policy and Financial Stability,” SSOAR (2024).

14 “DeFi platforms can comply with regulations without compromising privacy — Web3 exec,” Cointelegraph.

18 “Cryptocurrencies and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs),” Antiriciclaggio Compliance (2025).

16 “Privacy in DeFi: Importance, Challenges, Solutions,” Streamflow (2023).

19 “Towards an Effective Regulatory and Governance Framework for Central Bank Digital Currencies,” Stanford JBLP.

15 “Going mainstream: Cryptocurrency narratives in newspapers,” Wiley.

21 “Crypto, crime and control,” Global Initiative.

https://www.thestreet.com/crypto/investing/how-crypto-and-blockchain-challenge-centralized-power

https://repository.essex.ac.uk/33514/1/FinalCorrectionCopy_KellyCoulter_PhDthesis.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2096720921000166

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rise-decentralized-power-state-nations-corporations-age-punzano-z4x8f

https://cointelegraph.com/learn/articles/geopolitics-of-bitcoin-implications-global-power-dynamics

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/add%20to%20this%20.pdf

https://arch.astate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=clac-scrim-facpub

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/6b7192114808c5530793c66d1cdb4781f1e4431a

https://icoholder.com/blog/defi-privacy-under-threat-kyc-blacklists-and-censorship/

https://hackernoon.com/can-defi-achieve-compliant-privacy-without-sacrificing-its-decentralized-soul

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521924002370

https://stanford-jblp.pubpub.org/pub/regulatory-governance-framework-cbdc/release/2

https://www.bundesbank.de/en/press/speeches/are-crypto-assets-a-threat-to-financial-stability–908084

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/69c06ea05f652459b42d386e88c950fd4d607916

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781136401688/chapters/10.4324/9780203048986-11

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/a73af4c6e8df7aca177b5c6829c3a0a85c9e8b8f

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/149e7a557f6100e97dc1e996c265d560334ac770

http://berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/israel-studies-review/31/1/isr310104.xml

https://www.unibw.de/usable-security-and-privacy/publikationen/pdf/froehlich2021icbta.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949694224000269

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/21582440231217854

http://journal.iaincurup.ac.id/index.php/negrei/article/view/5527

https://www.onesafe.io/blog/implications-of-social-media-narratives-in-cryptocurrency

https://www.thomsonreuters.com/en-us/posts/investigation-fraud-and-risk/crypto-crime-caveats/

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/3f83538a8b95949538b110c28ada9dcd6144923d

https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:9901f078-17d2-4f63-be8d-4e07fbe0f373/files/swd375z124

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1351847X.2023.2284186?needAccess=true

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.814087/pdf

https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR3000/RR3026/RAND_RR3026.pdf

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13669870701746316

https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/pdf/2021/22/shsconf_eecme2021_01005.pdf

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03085147.2022.2091316?needAccess=true

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/02697580231215840

https://www.mdpi.com/2674-1032/3/2/14/pdf?version=1711530022

https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/12/2/33/pdf?version=1681566648

https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/ws/files/42792707/Accepted_Manuscript.pdf